Turtle Rescue Team Saves Snapper With Plenty of Backbone

A severed spinal cord is disastrous for people, but not so for some remarkable animal species.

A rescued snapping turtle named Funfetti provided living proof of that for members of the Turtle Rescue Team at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine.

Funfetti was discovered with severe injuries somewhere west of Raleigh and transferred to the Turtle Rescue Team in late April 2019. The consensus was that he had probably been hit by a car, and the damage was devastating.

Most creatures would be lucky to survive such injuries, says Greg Lewbart, professor of aquatic animal medicine at the CVM and a co-founder of the student-run Turtle Rescue Team,

“But it’s a snapping turtle,” Lewbart says, with a nod toward how tough these animals are. “In most cases this turtle would have been euthanized, but we always say, ‘treat the patient, not the lab results.’

“Funfetti showed spunk and fight from the beginning, and we later learned that at least some turtles can heal from a severed spinal cord injury.”

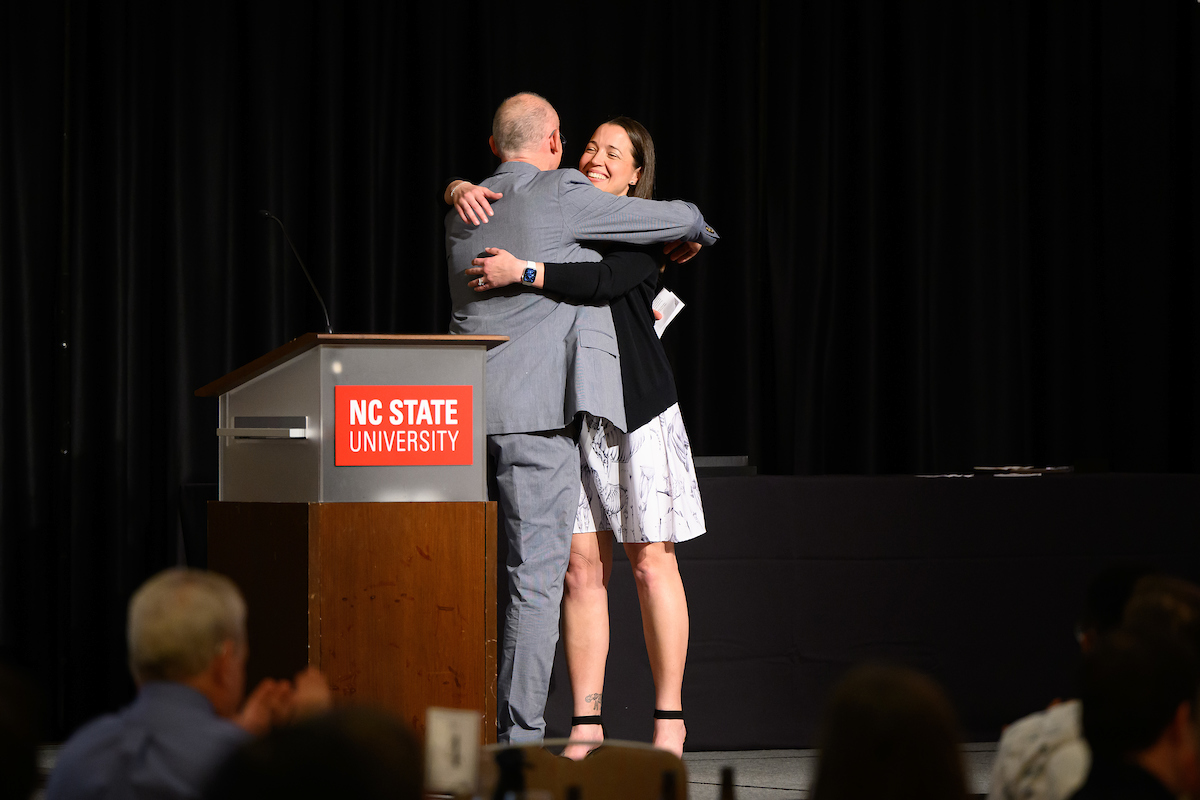

Lewbart credits Funfetti’s extraordinary recovery to months of dedicated nursing and rehabilitation efforts led by Ashley Kirby, the Carolyn Glass Turtle Rescue Team Intern, who oversees the work of students and volunteers who form the TRT staff.

Kirby’s is a new position created through donor support from Kerry Glass. Kerry, Carolyn’s mother, helped create the internship as a way to honor her late daughter, who was an exotic animal veterinarian interested in conservation.

As a CVM class of 2018 alumna, Kirby spent countless hours volunteering with the Turtle Rescue Team and now oversees its daily operations. The Turtle Rescue Team sees and treats over 300 wild turtles, reptiles and amphibians each year.

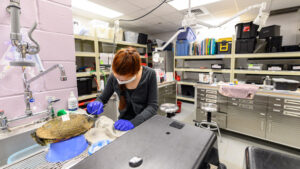

Kirby says that when Funfetti first came to the TRT, his injuries included a badly fractured carapace, or upper shell, exposed internal organ, and significant amounts of dead tissue and maggots, indicating that the wound was not fresh.

But that’s not all. Kirby says Brandi Clark, a student volunteer and member of the class of 2022, performed a triage exam on the snapper and noted he was particularly snappy — bright, alert, and responsive.

Funfetti showed spunk and fight from the beginning, and we later learned that at least some turtles can heal from a severed spinal cord injury.

That was a sign that Funfetti had plenty of fight. While that was a good thing for his prospects, it was a risky thing for his rescuers. After administering antibiotics and an anti-inflammatory medication, the team sedated the turtle for his safety and theirs. Clark then assessed his wounds, flushed them with saline and a medication to remove the maggots, and began to remove dead tissue.

It was the start of what would be a long and painstaking treatment process.

After his initial treatment was completed, Funfetti was sent home with a local rehabber the following month for continued rest, care and monitoring. TRT rehabilitation coordinators kept in regular contact with the rehabber and arranged for the turtle to return for a recheck. That August, Funfetti’s condition was not progressing as hoped and after another round of treatment and further examination, the full extent of the turtle’s injuries were discovered.

At this point, Kirby took a more active role in overseeing the turtle’s treatment, including consultation by the NC State Veterinary Hospital‘s neurology service, which recommended water therapy. This began a rehabilitation program that included taking Funfetti outdoors for 10 minutes of sunlight and exercising his rear legs each day. By October, the turtle was using his rear legs on his own and he was transferred to the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in November for further monitoring and care.

During his stay at the museum, Funfetti enjoyed an upgrade in his accommodations, including a larger tank, a UV-B light to more closely approximate sunlight and a varied diet. He continued to be treated for occasional infections, had dead tissue removed and continued to progress into the new year, although the healing process was slow.

With all the complications presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, by March Funfetti’s team had to reassess what to do.

“Based on COVID-19 precautions and stay-at-home orders,” Kirby says, “we determined it would be unlikely for Funfetti to have a follow up CT and neurological exam until at least June. In addition, we couldn’t guarantee daily care and monitoring in the event of an emergency. Since he was doing well and had been off of medications for a while, we decided to release him.”

On March 28, a microchip ID tag was implanted under Funfetti’s skin and he was released back into the wild.

“He was able to walk into the water and put weight on his rear limbs,” Kirby says. “Based on how well he did in rehabilitation, we hope he can continue to thrive.”

~Steve Volstad/NC State Veterinary Medicine