Stopping Foodborne Illnesses In Their Tracks

You’d hardly give it a second glance, this new equipment tucked away in the back of a lab on the fourth floor of the Research Building at North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), but it has the power to help the millions affected by foodborne illnesses each year.

About the size of an old-school Mac computer, the MiSeq System easily blends in with its surroundings in the lab of Siddhartha “Sid” Thakur, an associate professor of molecular epidemiology at the CVM. It looks similar to any lab machine found across campus. But it is here where hundreds of isolated pathogens will undergo whole genome sequencing and fed into a sharable worldwide database. The goal: identifying the pathogen early and preventing it from spreading.

It’s called GenomeTrakr. And the CVM is the only place you’ll find it in North Carolina.

“Just like you and I have our unique fingerprints, pathogens have their own fingerprints,” says Thakur, who is also the associate director at NC State’s Comparative Medicine Institute and leads its Emerging and Infectious Diseases Research Program. “When the fingerprints match, that means we have a culprit.”

In operation now at the CVM, GeomeTrakr, developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, is the first network of labs using whole genome sequencing to identify pathogens. Currently, it consists of 37 labs in the United States, mostly federal, state health and university labs, and 17 outside of the country. Prior to GenomeTrakr’s launch in 2012, the sources of many outbreaks, says Thakur, were commonly identified after the outbreak had been contained.

[pullquote color=”indigo”]”Just like you and I have our unique fingerprints, pathogens have their own fingerprints, when the fingerprints match, that means we have a culprit.” ~ Sid Thakur[/pullquote]

Now, genome sequences are identified, cataloged and shared through an easily accessible network, particularly helpful in pinpointing the source of an outbreak quickly, especially since most outbreaks occur over multiple states. The GenomeTrakr data is maintained at the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

According to the FDA, since its launch the network has sequenced over 61,000 isolates, including some of the most common sources of foodborne illnesses — Salmonella, Listeria and E. Coli. According to CDC estimates, each year 48 million Americans, or one in six, get sick by consuming contaminated foods or beverages.

GenomeTrakr’s impact has been swift; members of the GenomeTrakr network are sequencing more than 1,000 isolates a month. In 2014, the network was used to match food and environmental samples with human samples, pinpointing the source of a Listeria outbreak.

“It’s already proven to be a huge depository of rich information,” says Thakur. “Someone can match his isolate from a pig in Brazil and match it with a pig in Minnesota or Iowa. You have more information and it’s a very fast process.”

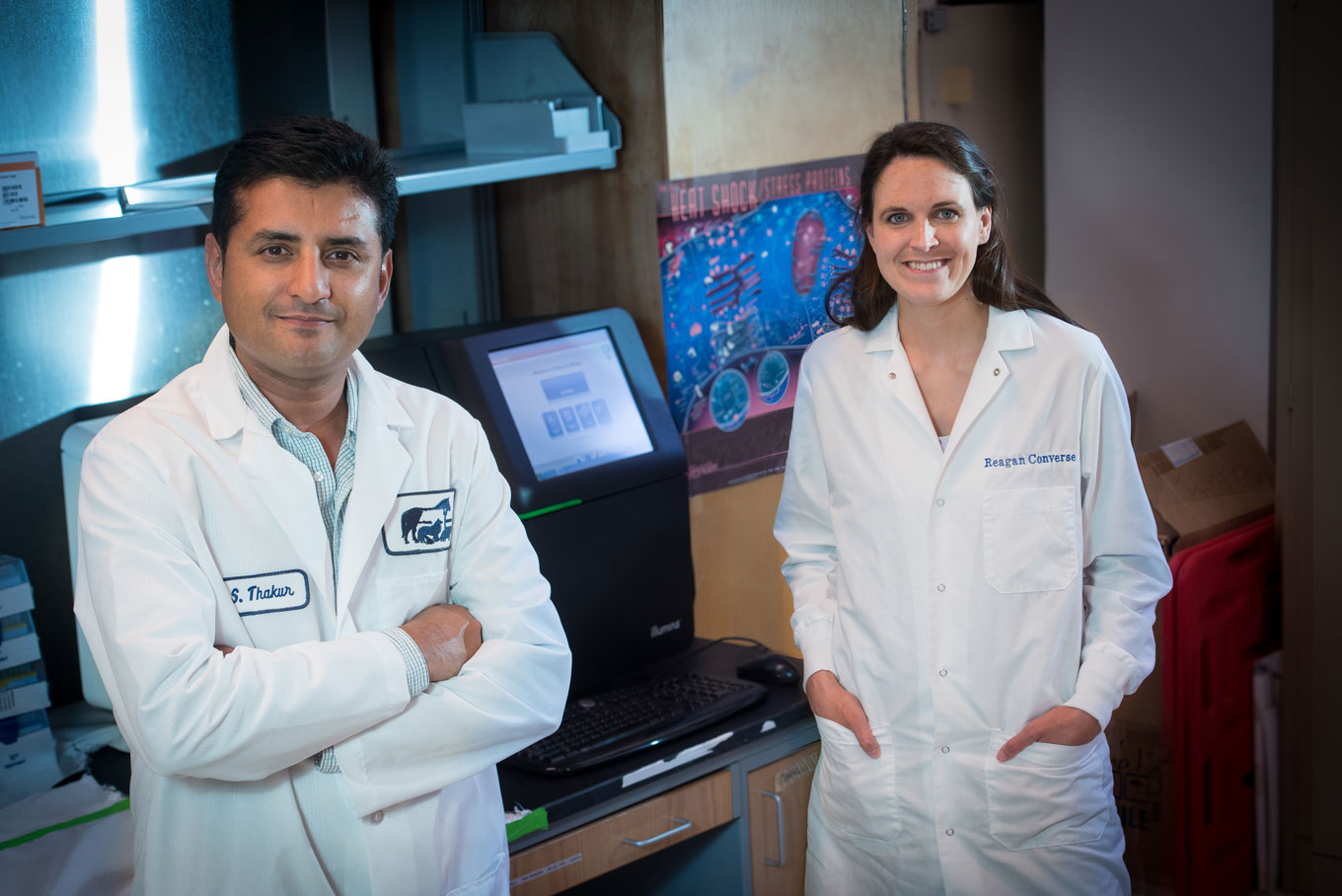

The effort to bring the GenomeTrakr program to the CVM started a year ago, as Thakur began meeting with Reagan Converse, the chief microbiologist at the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Food and Drug Protection Division. Converse had been eager to have her state government lab be a part of the program.

[pullquote color=”indigo”]“Being part of the GenomeTrakr program means we have access to a wealth of information about how pathogens we isolate from the food chain might be linked with state, national and international outbreaks.” ~Reagan Converse[/pullquote]

The project is conducted in close collaboration between the CVM and the NCDACR. The GenomeTrakr instrument is housed at the CVM and samples will be sequenced here, as Converse’s department will work closely with CVM on experimental design, analysis and data transfer.

“Whole genome sequencing is a powerful tool,” says Converse. “Being part of the GenomeTrakr program means we have access to a wealth of information about how pathogens we isolate from the food chain might be linked with state, national and international outbreaks.

“Ultimately, we will be able to pull dangerous food from the market earlier and reduce the public health impact.”

If not checked properly and quickly, foodborne illness outbreaks can go on for weeks and possibly months. For North Carolina, early detection is particularly key, as the state is one of the nation’s leaders in hog, chicken and turkey production. And as the GenomeTrakr network expands, it will get to a point where if there’s a new strain that pops up in some part of the world, the database will reveal if it’s something new or link it to something seen before, Thakur says.

Along with disease prevention, GenomeTrakr provides a wealth of information to those researching pathogens.

“That same profile that you got from a pig, we could find that in a tomato in Arkansas, and we could see that in lettuce in California and also in a chicken in Iowa,” says Thakur. “So then I would know that this particular bug I found in a pig has the ability to survive in three different types of products.”

But for Thakur, it all comes down to one thing: improving human health. His goal is to generate between 400 and 600 sequences a year. It is free to submit isolates and have them sequenced. Thakur hopes to collect a diverse group of samples reflecting multiple types of isolates and from sources ranging from other labs and hospitals to veterinary clinics.

“GenomeTrakr is working and its reach is massive,” says Thakur. “The proof is already in the pudding.”

~Jordan Bartel/NC State Veterinary Medicine